Dear friends,

Call it a penchant for melancholy, but I have come to see my affinity for the cold, dark days of December in a rather different light—as an invitation to join in the quiet chorus of groans of a world reduced to snow and splinter, awaiting its rebirth.

It is in this inward mimesis of the world’s quietude where I have learned perhaps how to pray the common prayer of creation, the prayer that places us in direct communion with each of God’s creatures.

Of course, such silent oratory does not only place us in communion with the meek things in nature. It must necessarily include, as well, the meek of the city, of the suburbs, of forgotten rural backroads. In short: the poor.

This, I think, is the true heart of the season of Advent—those four weeks of waiting, longing, fasting, groaning with the lowly that precede the celebration of Christ’s birth among them. We find it echoed in a song by Stephen Foster, the father of the Great American Songbook:1

Let us pause in life’s pleasures and count its many tears While we all sup sorrow with the poor: There’s a song that will linger forever in our ears; Oh! Hard Times, come again no more. ‘Tis the song, the sigh of the weary; Hard Times, Hard Times, come again no more: Many days you have lingered around my cabin door; Oh! Hard Times, come again no more.

But long before Foster penned these words, “the sigh of the weary” had found expression in another set of words: Kyrie eleison—Lord have mercy.

This prayer has initiated the celebration of the Holy Eucharist for centuries, and before that was found strung throughout the Hebrew psalms. It represents, perhaps, the primordial cry from the hidden depths of the soul.

In the classic Russian devotional text The Way of the Pilgrim, its anonymous author, a poor vagrant peasant, discovers exactly this while learning to pray unceasingly the Jesus Prayer. As he syncs the words Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me with his breathing, he comes to an insight much like the one above.

“[When]…I prayed with my heart,” he writes, “everything around me seemed delightful and marvelous. The trees, the grass, the birds, the earth, the air, the light seemed to be telling me that they existed for man’s sake, that they witnessed to the love of God for man, that everything proved the love of God for man, that all things prayed to God and sang His praise.”

As this pilgrim continues, he teaches the Prayer to all he meets—most of whom are as poor and sickly as himself—and they take it in with joy.

Upon meeting a county clerk, though, the pilgrim is delighted to hear the cleark tell him, “The mysterious sighing of creation, the innate aspiration of every soul towards God, that is exactly what interior prayer is.” The clerk would have been wise to stop there, but he concludes: “There is no need to learn it, it is innate in every one of us!”2

The man of high status knows that all creation groans and sighs—but he cannot hear it, nor has he allowed its ache to become his own. He has not aligned himself with the least of these among Christ’s brethren.

This month, as we find ourselves in this season of preparing the way for our rebirth in Spirit, let us heed the invitation of Foster to “pause in life’s pleasures”—even with the sirens urging our indulgence—and of this lowly pilgrim to learn to make that sigh our own.

WE ARE ALL HOMELESS

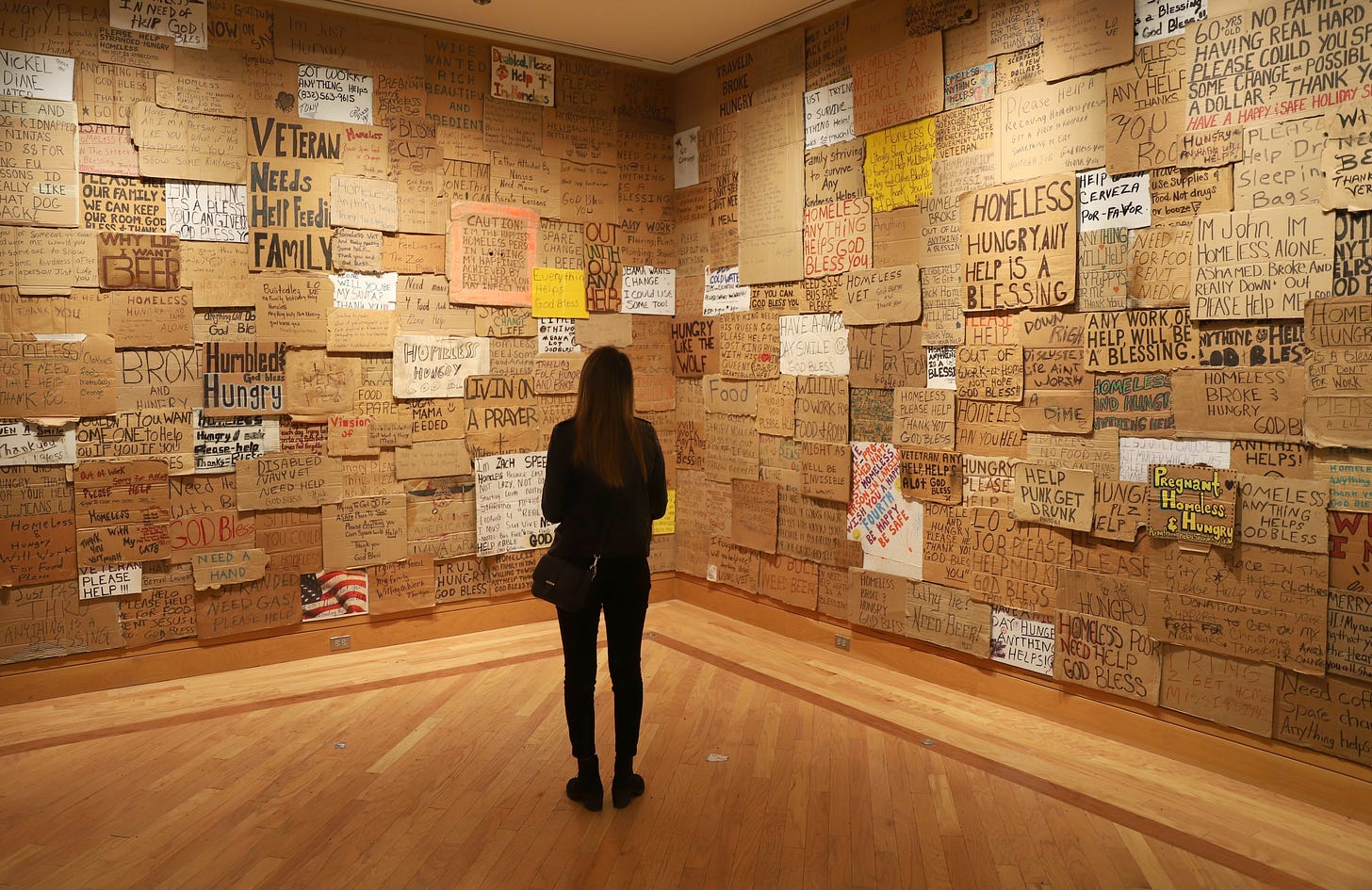

To say that the WE ARE HOMELESS project is “by” artist, professor, and film-maker Willie Baronet isn’t quite accurate. Rather, Baronet has sought to give voice to artists that often go unnoticed—the homeless. To that end, he began purchasing the signs of people he’d encounter on the street asking for change. Over the years, he’s assembled these signs into sprawling collages like the one above.

He describes the project in his own words thusly:3

The WE ARE ALL HOMELESS project began in 1993 due to the awkwardness I felt when I’d pull up to an intersection and encounter a person holding a sign, asking for help. Like many, I wrestled with whether or not I was doing good by giving them money. Mostly I struggled with my moral obligations, and how my own choices contributed in conscious or unconscious ways to the poverty I was witnessing. I struggled with the unfairness of the lives people are born into, the physical, mental and psychological handicaps. In my struggle, I avoided eye contact with those on the street, unwilling to really see them, and in doing so avoided seeing parts of myself. That began to change once I began asking them if they would sell their signs. My relationship to the homeless has been powerfully and permanently altered. The conversations and connections have left an indelible mark on my heart. I still wrestle with personal questions regarding generosity, goodness, compassion, and guilt. And what it means to be homeless: practically, spiritually, emotionally? Is home a physical place, a building, a structure, a house? Or is it a state of being, a sense of safety, of being provided for, of identity? I see these signs as signposts of my own journey, inward and outward, of reconciling my own life with my judgments about those experiencing homelessness.

Viewing the installations this project has yielded is like looking into a two-way mirror. On one viewing, we are confronted by our own guilt—the many times we’ve passed the homeless by without alms or attention. On another viewing, though, the humanity and the tenacity of the people behind the signs emerge. We find ourselves longing for the very same things they long for too: security, community, justice, Love.

In 2016, Baronet and a team of film-makers debuted a documentary, Signs of Humanity, detailing their interactions with people experiencing homelessness across the United States. You can stream it through Amazon Prime.

Mouchette by George Bernanos (1937)

I wasn’t familiar with French author Georges Bernanos’ novels until rather recently, when I happened upon his 1937 novel Mouchette (New York Review Books) on an end-cap at my local public library. Since then, I’ve learned just how much I’ve missed out on.

Best known for his novel Diary of a Country Priest (1936), Bernanos became a fierce critic of materialism and greed at the expense of the poor after fighting a campaign in World War I; residing in Spain under the control of Fascist dictator Francisco Franco; and residing once more under Fascist influence in Philippe Pétain’s France. “Bernanos was increasingly disillusioned by the spiritual bankruptcy of European politics,” writes Heather King, “and by the failure of his beloved Church to model the teachings of Christ.”4 Diary of a Country Priest seeks to demonstrate this at the societal level, but Mouchette’s scope is much smaller.

Mouchette is the 14-year-old daughter of alcoholics, is despised by her teacher and classmates, and is ridiculed by her townsfolk—all of whom are only slightly more well off than herself. Her whole existence seems mechanized towards humiliation. Even her name is shameful, translating to “little fly.” Devastation and scorn meet her at every turn, especially when a friend of her drunken father’s violates what purity she has left. The incident leaves her desperate for redemption and transcendence.

Though Bernanos’s short novel is gut wrenching—a tragedy in the strictest sense of the word—his Catholic, sacramental sensibilities are woven vividly throughout. To say he has adopted for himself a preferential option for the poor is not sufficient, for his concern is not in the poor as abstract objects of pity and charity, but as the people with whom Christ most identifies. He also seems to possess that gift that the world’s greatest Catholic writers (I’m thinking especially of Flannery O’Connor and Shūsaku Endō) seem to share in finding grace in the most forsaken circumstances.

Oh Me, Oh My by Lonnie Holley (2023)

Mount Meigs, Alabama Industrial School for Negro Children '64, they let me go They let me go from Mount Meigs, Alabama In 1964 But with some cuts and bruises that I would never forget Alabama Industrial School The hardship that the children was going through Children after children after children Picking cotton Toting those bales Bending our backs Hoeing up and down the ditches and the creeks

Lonnie Holley does not so much sing these words as drawl them slowly, as from his grandparents’ front-porch rocking chairs over a chaotic swirl of drums, electric guitar yelps, and saxophone swells. They introduce the fifth chapter in what one critic has called an “aural memoir”5 of Holley’s equally chaotic early life: Oh Me Oh My (Jagjaguwar, 2023).

Holley was born in 1950, when Jim Crow politics in his home state of Alabama were near their apogee. Make no mistake, then: The Mount Meigs, Alabama Industrial School for Negro Children was no more than a thinly veiled camp for forced labor. Holley arrived there at age 11. For four years his enslavers forced to pick 100 pounds of cotton a day. After a failed escape attempt, Holley was beaten within an inch of his life and thrown into a pile of rocks, “where, for three months, too weak and injured to walk, Holley crawled.”6 Reflecting further on this time of brutality, Holley sees the damage done to his physical body, but to his spirit also. He snarls later in the same track,7

They beat the curiosity out of me They beat it out of me They pushed it They knocked it They banged it Slammed it Damned it Damned the curiosity

Though his time at Mt. Meigs certainly represents “the most harrowing four years of [his] life”8, any of the other tribulations Holley had lived through up to this point would certainly have been enough. By the time he was 7, he’d been kidnapped by a burlesque dancer, exchanged for liquor, impaled through the head with an iron fire poker, struck by a car, and pronounced brain dead. By age 9, he had hopped trains until finding himself in New Orleans, and by 10 had been arrested after unwittingly violating the curfews set in place by Birmingham’s police commissioner Bull Connor.

In time, Hollie found himself reunited with his mother and the rest of his community. It was that return to love enabled him, perhaps, to set about the next phase of his life.

“Since 1979,” his official biography reads, “Holley has devoted his life to the practice of improvisational creativity.”9 That improvisational spirit (perhaps the pinnacle of curiosity in the arts) is now represented in his found-object junkyard sculptures, which have been featured in some of the world’s most impressive art galleries and museums.

Oh Me Oh My marks Holley’s seventh piece of recorded music. While he has managed to capture something cosmic, vital, yet personal in his visual art over all these years, the songs comprising Oh Me Oh My are perhaps the most lucid of those attempts. What’s more is that they verge on a vision that is prophetic—at once localized in time and eschatological in scope. In a duet with Bon Iver’s Justin Vernon, the two sing,10

Greatness come in the morning Kindness will follow your tears Greatness will come in the morning And dry them up Down through the years

I hope you will take these with you through the remainder of Advent, that they will challenge you and set something stirring within you, that they will attune your ear to the faint cry of Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me whispered through the snow and the bare trees that droop beneath it—but also in the cries of beggars, and in the cries of bodies whom bombs and bullets have ravaged. Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy.

Amen.

Foster, S. (1854). Hard times come again no more. https://songofamerica.net/song/hard-times-come-again-no-more/

The Way of a Pilgrim, and The Pilgrim Continues His Way. (R. M. French, Trans.). (1974). Seabury

Baronet, W. (n.d.). WE ARE ALL HOMELESS. Weareallhomeless.org. Retrieved December 6, 2023, from http://www.weareallhomeless.org/

King, H. (2018). Georges Bernanos. Catholiceducation.org. https://www.catholiceducation.org/en/culture/art/georges-bernanos.html

Schonfeld, Z. (2023, March 15). Oh Me Oh My. Pitchfork. https://pitchfork.com/reviews/albums/lonnie-holley-oh-me-oh-my/

Baszile, N. (2018). Lonnie Holley: One Man’s Trash Is Another’s Salvation. Thebittersoutherner.com. https://bittersoutherner.com/lonnie-holley-one-mans-trash-is-anothers-salvation

Holley, L. (2023). Mount Meigs [Recorded by L. Holley]. Jagjaguwar.

Ibid.

Landis, J. (2018, January 26). Bio. Lonnieholley.com. https://www.lonnieholley.com/blog/2018/1/26/bio

Holley, L. (2023). Kindness Will Follow Your Tears [Recorded by L. Holley & J. Vernon]. Jagjaguwar.